It was evening in late summer, not long after my arrival in Isfahan, when I drew aside the curtain of blue beads hanging across the doorway and stepped into the tea-house for the first time. The benches on each side of the passage were full. I walked uncertainly into the central room, looking for a place to sit.

— Michael Carroll, From a Persian Tea House: Travels in Old Iran

Actually, it was a morning in early spring, the first day of March 2025 and I was at ‘Teheran Station’, a Persian tea-house in a small Berkshire shopping mall. There wasn’t a curtain of blue beads at the entrance; instead, the doorway was a portal for admitting the artificial light of the shopping corridor. When I stepped in, there were no customers crowding benches or tables; picking a place to sit was a simple choice between a view of colourfully stocked shelves, and the ornate wall with the price list chalked in filigree script on blackboard.

I chose the filigree script, for its menu evocative of Old (and presumably also contemporary) Iran, including poetic-sounding items like cardamon and rose petal tea. When I ordered a coffee, one of the three women behind the counter noted that the Italian machine was broken but I was welcome to have a Turkish coffee. She then explained to a younger barista how to prepare this coffee in a brass pot.

Other than background music, for a while the place was quiet. But just as my coffee was brought to the table, scalding hot and brimming to the top of a green espresso cup, another customer walked in. She chose a seat facing the produce shelves, sitting diagonally from me, close to the door. Frail, petite, visibly at one with the world, this older woman struck me, in her contentment, as a projection of what I’d wish for my older self: not as I imagined I’d become, but what I thought I ought to become. In elective solitude over a coffee, just like now, but also quietly radiating some kind of acceptance, no longer unsettled in a myriad ways - including by misgivings about the amount of caffeine I was about to have.

Separated by an invisible time-wall, my older self and I are both wearing a blue dress. Hers is darker, of cut and pattern more conservative than mine, with buttons, smart V-collar, tiny white polka dots. Mine is sky-blue, dotted with tiny daisies, with a high waist and flouncy sleeves.

This dress dates back to the summer of 2020. I had bought it in one of those heart-stopping Andalusian towns with streets cobbled in white on black, and magnificently unassuming white-washed houses. Fuchsia-pink hibiscus and bougainvillea spilled over many of these gleaming walls, most of which were also decorated with roundels of artisan plates. Dreamy doorways, hand-painted in aquatic colours with marine or astral motifs, opened to the street as boutiques or diminutive cafes with just a couple of tables and stools.

We were browsing one of those souvenir shops that strive to provide a bedazzling range of craft products, none made of plastic and apparently none mass-produced in China. The objects beckoned the tourist to touch, handle, imagine the use of… - while drifting into momentary fantasies of a life lived in this sun-beaten land. By a large basket of neatly rolled hand-woven rugs, terracotta trinkets, lavender and rosa-mosqueta cosmetic products, two dresses hung prosaically from hooks in the stone wall, like laundry stretched to dry indoors: one pale grey and the other sky blue, both speckled with daisies. The sky blue one refracted the sunshine streaming through the open doorway, the ripples of light on fabric echoing the cerulean doorframe. It was a dress that promised an eternal summer of deep and serene skies above a blue-tiled swimming pool, like the one tucked below the stone terrace of our holiday villa overlooking the distant sea.

Since that summer, the solar promises of this dress stayed close to my skin, any time and anywhere I’d wear it. So now, facing the woman who could be my older self, I’m wondering what stories hide between her polka dots, as she sits for a quiet break in this British-Persian tea-house?

I didn’t know at the time that 2020 would see our final family holiday, in what was an already momentous summer straining against the borders of lockdowns. It was a journey that almost did not happen. The night before the epic drive from England to Spain via France, plugged into news of Covid threatening to tighten its barely loosened grip once more, beginning with Barcelona, we were still unsure about setting off. By that point in July travel across Europe was permitted, with the caveat that borders could close unexpectedly, and we had already cancelled the Portuguese leg of the journey.

With four days of stopovers in picturesque towns along the French and Spanish coast, we made it to our destination, an Andalusian nature reserve above the Alboran Sea. By the time we returned to England however, Covid was already slamming shut the gates of many Spanish cities, before creeping up towards the heart of Europe. In our wake, as we traversed the lush Atlantic shores of Basque Country and France, it didn’t take long for further regional lockdowns to take hold. Meanwhile back in England, the ‘Eat Out to Help Out’ British summer was in full swing and our fear of not being allowed ‘in’ turned unfounded - nobody cared to check our temperature or Covid certificates (the norm at the entrance to public places in Spain and France at the time).

I brought a host of mixed memories from that scorching summer and the blue dress somehow featured in all of them. The strangest and most powerful of these is simple: despite, or perhaps because of, the intense beauty and tranquility of our Andalusian stay, like nothing I have experienced anywhere before or since - and which I decidedly did not want to leave behind - I felt irrevocably trapped. I hated myself for this feeling, which was so overwhelming that by afternoon on any given day, I was close to tears: I felt frustrated but also spoilt, ungrateful, ridiculous, volatile; that I did not deserve to spend two weeks in what could only be described, albeit tritely, as earthly paradise. It’s not that I was bored: this pocket of time off from intense work, from the pandemic, was much needed. I swam at dawn, I read, I wrote, I was entertained by my kids frolics in the swimming pool. I cooked wholesome food and breathed air scented with wild thyme and the song of cicadas. I walked my dog in groves of olive, carob and fig trees, I delighted in spotting wild cats and colourful reptiles amongst Aleppo pines. All this with the luminous expanse of the sea constantly in sight. And still I felt trapped.

As I fidget with my notebook waiting for my coffee to cool, I notice there is now a cafetière on my distant companion’s table, which she ignores. Wearing dark sunglasses (which she will not remove while at the tea-house) and a straw hat with narrow borders over a grey bob, she is lost in thought. Her shielded gaze transcends the doorway into the diffused haze of milky neon and filtered daylight. It’s a weekday and the shoppers are few, there isn’t really anything to see. The smile persisting dreamily on her lips comes from somewhere else. I wonder about her memories of summer holidays. Where was she between the lockdowns of 2020, and with whom? Did she risk travel abroad, a crowded ‘staycation’, or just ‘eating out to help out’?

My own sunglasses are buried in the debris of a royal blue tote painted with Van Gogh’s mauve and violet irises. This year’s flurry of art-themed accessories on the high street has rather beguiled me from my own personal lockdown. The tote, for its painted irises, is one of several merchandise items I have accumulated this spring for the escapist memories they conjure of the Louvre, the Uffizi or the Musée d’Orsay.

When the lady in blue walked in here for her coffee, she had positioned her foldable shopping trolley carefully, deliberately, alongside her chair. The trolley seemed empty. Later, I noticed its little black wheels neatly tucked under the table, next to her stockinged feet in smooth black ballerinas, perfectly aligned. I look down at my own feet, bare in soft, pink strapless flats from last summer’s Accessorize sale, then busy myself some more with my notebook. I notice, with self-deprecating dismay, that it, too, sports a Van Gogh design, this time of sunflowers embossed into a yellow cover and painted as motif on the fore-edge of pages.

Without looking up, I remain aware of the lady’s continued, slightly bemused, contemplation. Her table is by the shelves stocked with rose-petal and quince preserve, Ahmad Tea boxes in deep reds and gold, pots of multi-fragrant honey, tahini, halwa, and bottles of flower essence: orange blossom, vanilla, rose. In front of her and between us, there’s an island of faux-brass souk pots: Turkish delight in all the colours of the rainbow, olives in hues of green to purple-black, translucent pieces of dried fruit - cubes of yellow pineapple, curled slivers of bright orange mango - earthy figs and three kinds of glossy dates, candied almonds, crystallised ginger, walnut halves shaped like imperfect little brains. But she never turns her gaze to any of these wonders and away from the door. As I finish my coffee and shut my notebook, her cafetière is still untouched.

Perhaps we are both thinking of Iran. Personally, I drift to how once in the port of Sharjah, in the UAE, I could sense the looming presence of this country, massive, potent, almost within reach across the Persian Gulf. Cargo for re-export rolls daily from Iran into the UAE: fresh and dried fruit, nuts and vegetable produce; dairy; crustaceans; building materials (cement, masonry, ceramics); petrochemicals.

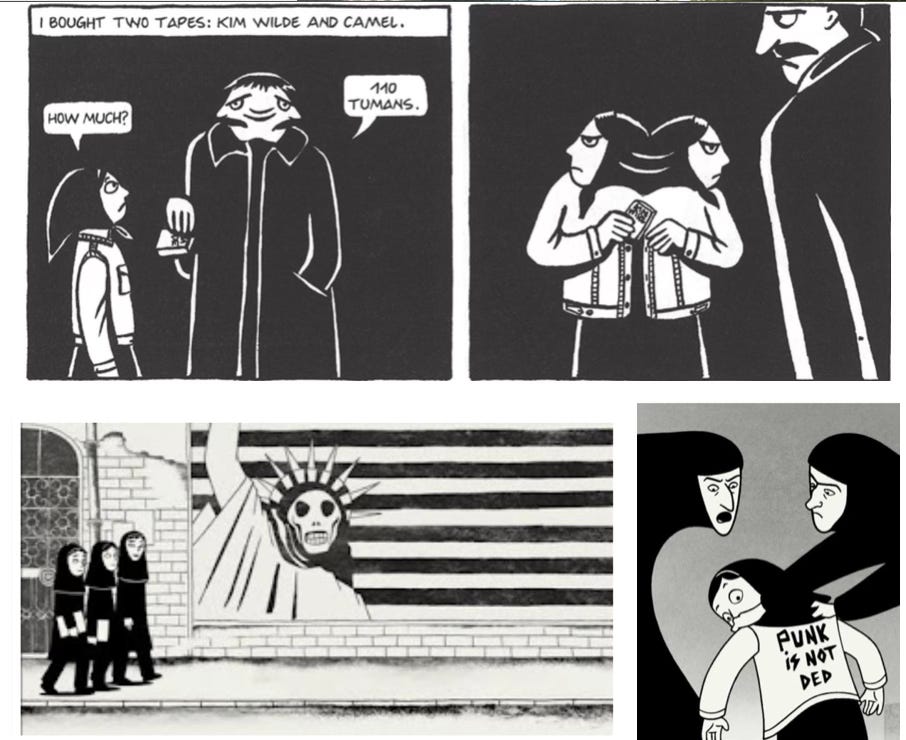

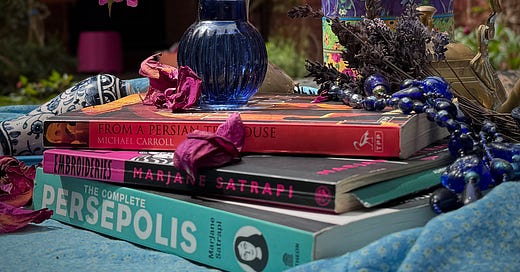

I also drift back to reading Persepolis in Paris, where it came out in 2000. Persepolis is Marjane Satrapi’s first graphic autofiction - her moving, tragic but also humorous memoir of growing up under the veil of the Iranian Revolution and later, the Iraq-Iran war. The second volume dwells on negotiating culture shock and freedom as a teenager posted by her parents to Europe in a bid to preserve her personal freedom.

Persepolis is now an established classic amongst teachers and students of the International Baccalaureate English syllabus. Satrapi has also reworked it into a highly successful animated film. Writing this, I discovered Woman, Life, Freedom, her recent collaboration with Iranian activists, artists, journalists and academics, foregrounding the feminist force behind the current revolution, in solidarity with the Iranian people. I would also recommend Satrapi’s lively Embroideries, for its decidedly subversive female voice, a ‘humorous and enlightening look at the sex lives of Iranian women’ in an afternoon of tea-drinking and talking, starring the author’s own ‘tough-talking grandmother, stoic mother, glamorous and eccentric aunt and their friends and neighbours.’1

I also remember Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe’s six year ordeal in arbitrary detention in Iran, separated from her husband and child until March 2022. How she spoke of her struggle to adjust to the taste and pace of freedom. And her story of how reading ‘sustained her sense of freedom’, particularly the illicit books circulated in Evin prison, for instance when ‘There was a long waiting list of inmates wanting to read [The Handmaid’s Tale], as well as one of the guards.’2

I take a moment to recall something of my own relationship with geopolitical boundaries, with the taste of freedom afforded by illicit reading,3 and how I also didn’t know what to do with freedom when I first experienced it as teenager. To quote the taxi driver who took me to Bucharest airport in the stifling, agitated summer of 1990, I jumped ‘out from the frying pan’ of the 1989 Romanian Revolution straight ‘into the fire’ of the Belfast Troubles. Perhaps I was fortunately naive in how at first I embraced freedom as dazzling, rather than overwhelming, as it must be for those emerging, like Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, from incarceration. Perhaps, for all its pitfalls, I benefitted from the guilessness of being brought up with barely a glimpse beyond the walls of my mountain town, in an iron-curtained country where ‘migrating’ from one region to another was regulated and politically suspicious. I threw myself into my new life with the zest of carpe diem at its most glorious. You could hear it in my voice in interviews (at the time, a Romanian child abroad was a political curiosity). But much like Satrapi, I was also lucky enough to have a degree of adult protection, however flawed and volatile, as I was moved from one host to another, then joined the school where, nurtured by teachers and new friendships, I was set up to take off on my own.

‘Freedom is never free’, Deborah Levy observes in her own tale of starting over - also more than once:‘anyone who has struggled to be free knows how much it costs’.4 Just as for Levy, Satrapi and millions of people young or old who joined diaspora streams across time, the cost of my freedom was homeland and its languages (three), foundational relationships, my home family. But I was also able to grow into new families, out of close friendships in Northern Ireland, England, France, Italy - and of course, the family I would precariously built for and around my own children.

This story today is a pin I’m dropping on the map of my world: here it lands, in this most unlikely setting, a Persian tea-house in a small Berkshire shopping mall. The pin bleeds into memories of stepping over the threshold of totalitarianism, into the fast traffic of culture shock and opportunities. These memories skid over decades before landing temporarily on sunlit streets where masked tourists take time out between lockdowns in stifling, perhaps contagious, heat. But I won’t allow my mind to wander too far from the comfort of my Turkish coffee. It’s quite enough to think that while I’ve never come physically closer to Iran than in the port of Sharjah, the stories of a country, as they reach us through fiction, memoir, the news, are as close as we get to travelling there, and through that, to understanding a little more about where we come from, and what we might become.

A gold chain escapes the V-collar of the navy blue dress worn by the lady in blue, and I can see a wedding ring hanging from it. I notice a watch around her right wrist, too, and thin bracelets which glint a little. My own necklace has a cut-glass bright blue stone, tear-shaped, from a recent trip to Rome. I don’t wear a wedding ring but those who sometimes hold my hand know my daisy chain of grief.

As she looks on, her coffee surely cold by now, the woman who could be my older self is still smiling softly, at nothing in particular. I am convinced the smile isn’t something she does, but who she is. It has become her. Paying my bill, I leave ‘Teheran Station’ carrying the hope that I might too, someday, cross that border to where a quiet smile becomes what I am.

What if freedom isn’t only about where we are, historically, geographically, materially - but also about where a place, an object, a book, an encounter, can take us? And what if, as Eastern philosophy and anyone whose movement has ever been constrained will insist, freedom is, first of all, an attitude?

In the tea-house the pool will be still, the blue bead curtain across the doorway quite motionless; and most people would say, if they were asked, that there was no-one in the tea-house at all.5

…but if anyone recognises the Lady in Blue, please get in touch. Thank you for reading :)

Penguin and Waterstones blurb for Embroideries, by Marjane Satrapi.

‘Escape to Another World’, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/nov/27/nazanin-zaghari-ratcliffe-on-reading-in-prison-iran-booker-prize

in my case, this consisted of French existentialist writers and philosophers

The Cost of Living, Things I Don’t Want to Know and Real Estate form Levy’s living autobiography trilogy.

Michael Carroll: From a Persian Tea-House, page 209

I love how you draw the threads of place, time and memory together here.

This was an exquisite trip. I felt I was there with you, smelling that coffee. ♥️♥️♥️